Clean Architecture

Part 1: Introduction

#1 What is Design and Architecture?

- The word Architecture get a lot of misunderstanding: it is often used in the context of something at a high level details (totally divorced from the low level details).

- The low-level and the high-level decisions are part of the whole. They form continuous fabric that defines the shape of the system, you can't have one without the other.

The goal of software architecture is to minimize the human resources required to build and maintain the required system.

- The best option is for the development organization to recognize and avoid its own overconfidence and to start taking the quality of its software architecture seriously.

#2 A Tale of Two Values

- Every software system provides 2 different values to the stakeholders:

- Behaviour

- Architecture/Structure Unfortunately, software developers either focus on one to the exclusion of the other or focus on the lesser of the two values.

Behaviour

- Programmers make machines behave in a way that makes or saves money for the stakeholders by helping the stakeholders develop a functional specification, or requirements document.

- Then they write the code that causes the stakeholder's machines to satisfy those requirements

- When the machine violates those requirements, programmers get their debuggers out and fix the problem.

Architecture

- Software must be easy to change. The difficulty in making such a change should be proportional only to the scope of the change, and not to the shape of the change.

- The problem is the architecture of the system. The more it prefers one shape over another, the more likely new features will be harder and harder to fint into that structure.

The Greater Value

-

There are systems that are practically impossible to change, because the cost of change exceeds the benefit of change.

→ The Greater value is the Architecture.

Eisenhower's Matrix

- Those things that are urgent are rarely of greate importance, and those things that are important are seldom of great urgency.

- Behavior is urgent but not always particularly important.

- Architecture is important but never particularly urgent.

Part 2: Starting with the Bricks: Programming Paradigms

#3 Pradigm Overview

Structured Programming

- Discovered by Edsger Wybe Dijsktra in 1968, He showed that the use of goto statements is harmful to program structure.

Structured programming imposes discipline on direct transfer of control.

Object-Oriented Programming

- Discovered two years earlier in 1966 by Ole Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard, They noticed that the function call stack frame in the ALGOL language could be moved to a heap, thereby allowing local variables declared by a function to exist long after the function returned.

Object-oriented programming imposes discipline on indirect transfer of control.

Functional Programming

- Has only recently begun to be adopted, was the first to be invented and the direct result of the work of Alonzo Church.

- A functional language has no assignment statement.

Functional programming imposes discipline upon assignment.

#4 Structured Programming

- Dijkstra realized that these “good” uses of goto corresponded to simple selection and iteration control structures such as if/then/else and do/while. Modules that used only those kinds of control structures could be recursively subdivided into provable units.

- The very control structures that made a module provable were the same minimum set of control structures from which all programs can be built. Thus structured programming was born.

- Structured programming allows modules to be recursively decomposed into provable units, which in turn means that modules can be functionally decomposed. That is, you can take a large-scale problem statement and decompose it into high-level functions. Each of those functions can then be decomposed into lower-level functions, ad infinitum.

- Structured programming forces us to recursively decompose a program into a set of small provable functions. We can then use tests to try to prove those small provable functions incorrect. If such tests fail to prove incorrectness, then we deem the functions to be correct enough for our purposes.

Software architects strive to define modules, components, and services that are easily falsifiable (testable). To do so, they employ restrictive disciplines similar to structured programming, albeit at a much higher level.

#5 Object-Oriented Programming

- Object-Oriented is "the combination of data and function" or "a way to model the real world".

#6 Encapsulation

- OO languages provide ease and effective encapsulation of data and function.

- The way encapsulation is partially repaired is by introducticing the public, private, and protected keywords into the language.

OO certainly does depend on the idea that programmers are well-behaved enough to not circumvent encapsulated data. Even so, the languages that claim to provide OO have only weakened the once perfect encapsulation we enjoyed with C.

Inheritance

- Inheritance is simply the redeclaration of a group of variables and functions within an enclosing scope. This is something C programmers were able to do manually long before there was an OO language.

We can award no point to OO for encapsulation, and perhaps a halfpoint for inheritance. So far, that’s not such a great score. But there’s one more attribute to consider.

Polymorphism

- polymorphism is an application of pointers to functions. Programmers have been using pointers to functions to achieve polymorphic behavior since Von Neumann architectures were first implemented in the late 1940s.

- OO languages may not have given us polymorphism, but they have made it much safer and much more convenient.

OO is the ability, through the use of polymorphism, to gain absolute control over every source code dependency in the system. It allows the architect to create a plugin architecture, in which modules that contain high-level policies are independent of modules that contain low-level details.

#6 Functional Programming

- Variables in functional languages do not vary.

- All race conditions, deadlock conditions, and concurrent update problems are due to mutable variables. You cannot have a race condition or a concurrent update problem if no variable is ever updated. You cannot have deadlocks without mutable locks.

- All the problems we face in applications that require multiple threads, and multiple processors cannot happen if there are no mutable variables.

- Structure programming is discipline imposed upon direct transfer of control.

- Object-oriented programming is discipline imposed upon indirect transfer of control

- Functional programming is discipline imposed upon variable assignment.

The rules of software are the same today as they were in 1946,

when Alan Turing wrote the very first code that would execute in an electronic computer.

The tools have changed, and the hardware has changed, but the essence of software remains the same.

Software is composed of sequence, selection, iteration, and indirection.

Nothing more. Nothing less.

Part 3: Design Principles

- The S.O.L.I.D principles tell us how to arrange our functions and data structures into classes, and how those classes should be interconnected.

- A class is simply a coupled grouping of functions and data. The SOLID principles apply to those groupings.

The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

An active corollary to Conway's law:

The best structure for a software system is heavily influenced by the social structure of the organization that uses it so that each software module has one, and only one, reason to change.

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

For software systems to be easy to change, they must be designed to allow the behavior of those systems to be changed by adding new code, rather than changing existing code.

The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

To build software systems from interchangeable parts, those parts must adhere to a contract that allows those parts to be substituted one for another.

The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Software designers should avoid depending on things that they don't use.

The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

The code that implements high-level policy should not depend on the code that implements low-level details. Rather, details should depend on policies.

#7 The Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

A module should be responsible to one, and only one, actor.

- SRP is about functions and classes but it reappears in a different form at two more levels:

- At the level of components, it becomes

the Common Closure Principle. - At the level of architecure, it becomes

the Axis of Changeresponsible for the creation of Architectural Boundaries.

- At the level of components, it becomes

#8 The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

A software artifact should be open for extension but closed for modification.

- The behavior of a software artifact ought to be extendible, without having to modify that artifact.

- The goal is accomplished by partitioning the system into components, and arranging those components into a dependency hierarchy that protects higher-level components from changes in lower-level components.

#9 The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

- The LSP can and should be extended to the level of architecture. A simple violation of substitutability, can cause a system's architecture to be polluted with a significant amount of extra mechanisms.

#10 The Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

- Depending on something that carries baggage that you don't need can cause you trouble that you didn't expect.

#11 The Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

- The most flexible systems are those in which source code dependencies refer only to abstractions, not to concretions.

- Don't refer to volatile concrete classes, Refer to abstract interfaces instead.

- Don't derive from volatile concrete classes.

- Don't override concrete functions.

- Never mention the name of anything concrete and volatile.

- The way the dependencies cross that curved line in one direction, and toward more abstract entities, will become a new rule that we will call the

Dpendency Rule.

Part 4: Component Principles

SOLID principles tell us how to arrange the bricks into walls and rooms. Component principles tell us how to arrange the rooms into buildings.

#12 Components

- Components are the smallest entities that can be deployed as part of a system.

- Components can be linked together into a single executable, or they can be aggregated together into a single archive.

- The dynamically linked files, which can be plugged together at runtime, are the software components of architectures.

#13 Component Cohesion

REP (The Reuse/Release Equivalence Principle)

- People who want to reuse software components cannot/will not do so unless those components are tracked through a release process and are given release numbers.

- This not simply because without release numbers there would be noway to ensure that all the reused components are compatible with each other, but also because that software developers need to know when new releases are coming, and which changes those new releases will bring.

- The release process must produce the appropriate notifications and release documentation so that users can make informed decisions about when and whether to integrate the new release.

→ REP means that the classes and modules that are formed into a component must belong to a cohesive group, and there must be some overaching theme or purpose that those modules all share. - Classes and modules that are grouped together into a component should be reusable together. The fact that they share the same version number and the same release tracking, and are included under the same release documentation should make sense both to the author and to the users.

- This is a weak advice because it is hard to precisely explain the glue that holds the classes and modules together into a single component, But the principle itself is important, because violations are easy to detect/don't "make sense".

CCP (The Common Closure Principle)

- As the SRP (Single Responsibility Principle) says that a class shoudl not contain multiple reasons to change, so the CCP (Common Closure Principle) says that a component should not have multiple reasons to change.

- If the code in an application must change, you would have that all of the changes occur in one component, rather than being distributed across many components. And you need only to redeploy the one changed component.

- If two classes are so tightly bound, either physically or conceptually, that they always change together, then they belong in the same component. This minimizes the workload related to releasing, revalidating, and redeploying the software.

- When a change in requirements comes along, that change has a good chance of being restricted to a minimal number of components.

Gather together those things that change at the same times and for the same reasons.

Separate those things that change at different times or for different reasons.

CRP (The Common Reuse Principle)

- CRP states that classes and modules that tend to be reused together belong in the same component.

- Reusable classes collaborate with other classes that are part of the reusable abstraction. CRP states that these classes belong together in the same component. In such a component we would expect to see classes that have lots of dependencies on each other.

- CRP also tells us which classes not to keep together in a component. When one component uses another, a dependency is created between the components. Because of that dependency, every time the used component is changed, the using component will likely need corresponding changes.

- We want to make sure that the classes that we put into a component are inseparable that it is impossible to depend on some and not on the others.

- CRP tells us more about which classes shouldn't be together than about which classes should be together.

→ CRP says that classes that are not tightly bound to each other should not be in the same component. - While ISP advises us not to depend on classes that have methods we don't use, The CRP advises us not to depend on components that have classes we don't use.

Don't depend on things you don't need.

The Tension Diagram For Component Cohesion

- The three cohesion principles tend to fight each other: The REP and CCP are inclusive principles (both tend to make components larger). The CRP is an exclusive principle (driving components to be smaller)?

- Generally, projects tend to start on the CCP and CRP where the only sacrifice is reuse. As the project matures, and other projects begin to draw from it. the project wil slide to REP.

#14 Component Coupling

A problem occurs in development environments where many developers are modifying the same source files: weeks go by without the team being able to build a stable version of the project and everyone keeps on changing their code trying to make it work with the last changes that someone else made.

Two solutions to this problem have evolved: The weekly build and Acyclic Dependencies Principle.

The weekly build

- In the traditional weekly build cycle, developers work independently for four days before integrating changes on Fridays.

- As projects grow, the integration process spills into Saturdays, prompting a shift to earlier integration days.

- This compromises team efficiency, leading to a switch to a biweekly build schedule. However, challenges persist with project size, creating a crisis. Lengthening the build schedule increases risks, complicating integration and testing while undermining the benefits of rapid feedback.

Eliminating Dpendeny Cycles

- To address integration challenges, partition the development environment into releasable components. Developers or teams manage these components, releasing functional versions for others to use. Teams independently decide when to adopt new releases, avoiding immediate dependencies.

- This decentralized approach enables incremental integration, eliminating the need for a simultaneous, collective integration point.

- Managing the dependency structure is critical to prevent cyclical dependencies and associated integration issues.

Top-Down Design

- The component structure of a system evolves rather than being designed top-down. Contrary to expectations, component dependency diagrams primarily serve buildability and maintainability, not functional descriptions.

- They emerge as the system grows to manage dependencies, avoiding integration challenges. Architects use principles like SRP and CCP to collocate changing classes.

- The focus is on isolating volatility, preventing unstable components from impacting stable ones. The graph adapts with the application's growth, incorporating CRP for reusability and applying ADP to address cycles. Designing the component structure before classes is impractical, as it may overlook essential principles and result in dependency cycles.

The Stable Dpendencies Principle

- By conformiing to the CCP (Common Closure Principle), we create components that are sensitive to certain kinds of changes but immune to others.

- Any component that we expect to be volatile should not be depended on by a component that is difficult to change.

- By conforming the Stable Dependencies Principle (SDP), we ensure that modules that are intended to be easy to change are not depended on by modules that are harder to change.

Stability�

- Stability has nothing directly to do with frequency of change.

- To make a software component difficult to change, you need to make lots of other software components depend on it.

The Stable Abstractions Principle

Where Do We Put The High-Level Policy?

In system design, stability for high-level architecture is vital, while volatility caters to rapid changes. Abstract classes, aligned with the Open/Closed Principle, offer flexibility without compromising stability—a key balance in system design.

Introducing The Stable Abstractions Principle

- The Stable Abstractions Principle (SAP) sets up a relationship between stability and abstractness.

- A stable component should also be abstract so that its stability does not prevent it from being extended

- An unstable component should be concrete since it its instability allows the concrete code within it to be easily changed.

Part 5: Architecture

#15 What is Architecture

- Software architects are the best programmers, and they continue to take programming tasks because they cannot do their jobs properly if they are not experiencing the problems that they are creating for the rest of the programmers.

- The goal of software architecture is not to make the system work properly. It certainly does, but that role is passive and cosmetic, not active or essential.

- Systems troubles do not lie in their operation, rather they occur in their deployment, maintenance, and ongoing development.

- The primary purpose of architecture is to support the life cycle of the system.

→ Good architecture makes the system easy to understand, easy to develop, easy to maintain, and easy to deploy. The ultimate goal is to minimize the lifetime cost of the system and to maximize programmer productivity.

Development

- A software system that is hard to develop is not likely to have a long and healthy lifetime, here is where the architecture comes to make the system easy to develop, for the team(s) who develop it.

- Many systems lack good architecture, likely because they started with a small team of developers working together to develop a monolothic system without well-defined components or interfaces, in other words they were begun with no architecture because the team was small and did not want the impediment of a superstructure.

- On the other hand, a system developed by different teams cannot make progress unless the system is divided into well-defined components with reliably stable interfaces.

- If no other factors are considered, the architecture of that system will likely evolve into a component per team and such architecture is not likely to be the best architecture for deployment, operation, and maintenance of the system.

Deployment

- To be effective, a software system must be deployable.

- The higher the cost of deployment, the less useful the system is.

- The goal of a software architect is to make a system that can be easily deployed with a single action.

- In the early development of a system, the developers may decide to use a "micro-service architecture" and they may find that this approach makes the system very easy to develop since the component boundaries are very firm and the interfaces relatively stable. But when deploy time comes they may discover that the number of micro-services has become daunting, and the configuration between them may also turn out to be a huge source of errors.

Operation

- The impact of architecture on system operation is the least dramatic compared to the impact of architecture on development, deployment, and maintenance.

- An architecture that is well tuned to the operation of the system is desirable, but the cost equation leans more toward development, deployment, and maintenance.

- The architect of the system should elevate the use cases, the features, and the required behaviors of the system to first-class entities that are visible landmarks for the developers.

A good software architect communicates the operational needs of the system.

Maintenance

- Maintenance is the most costly aspect of all the 4 software system aspects.

- A carefully thought-through architecture vastly mitigates these costs. By separating the system into components, and isolating those components through stable interfaces, it is possible to illuminate the pathways for future features and greatly reduce the risk of inadvertent breakage.

Keeping Options Open

- The way you keep software soft is to leave as many options open as possible, for as long as possible. The options that we need to leave open are the details that don't matter.

- All software systems can be decomposed into two major elements:

- Policy, which embodies all the business rules and procedures. It's where the true value of the system lives.

- Details, which is necessary to enable humans, other systems, and programmers to communicate with the policy, but that do not impact the behavior of the policy at all.

The goal of the architect is to create a shape for the system that recognizes policy as the most essential element of the system while making the details irrelevant to that policy.

This allows decisions about those details to be delayed and deferred.

A good architect maximizes the number of decisions not made.

#16 Independence

As mentioned before, a good architect must support the use cases, operation, maintenance, development, and deployment of the system.

Use Cases

- The architecture of the system must support the intent of the system. However, architecture does not wield much influence over the behaviour of the system.

- The most important thing a good architecture can do to support behaviour is to clarify and expose that behavior so that the intent of the system is visible at the architectural level.

Operation

- Architecture plays a more substantial, and less cosmetic, role in supporting the operation of the system.

- A system that is written as a monolith, and that depends on that monolothic structure, cannot easily be upgraded to multiple processes, multiple threads, or micro-services should the need arise.

- An architecture that maintains the proper isolation of its components, and does not assume the means of communication between those components, will be much easier to transition through the spectrum of threads, processes, and services as the operational needs of the system change over time.

Development

Conway's law says:

Any organization that designs a system will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

- A system that must be developed by an organization with many teams and many concerns must have an architecture that facilitates independent actions by those teams, so that the teams do not interfere with each other during development.

- This is accomplished by properly partitioning the system into well-isolated, independently developable components.

Deployment

- The architecture also plays a huge role in determining the ease with which the system is deployed.

- A good architecture does not rely on dozens of little configuration scripts and property file tweaks. A good architecture helps the system to be immediately deployable after build.

- This is achieved through the proper partitionning and isolation of the components of the system, including those master components that tie the whole system together and ensure that each component is properly started, integrated, and supervised.

Leaving Options Open

- A good architecture balances all of these concerns with a component structure that mutually satisfies them all but the reality is that achieving this balance is pretty hard.

- Most of the time we don't know what all the use cases are, nor do we know the operational constraints, the team structure, or the deployment requirements. Even if we did know them, they will inevitably change as the system moves through its life cycle.

→ In the real world, the goals we must meet are indistinct and inconstant. - Some principles of architecture are relatively inexpensive to implement and can help balance those concerns, even when you don't have a clear picture of the targets you have to hit. Those principles help us partition our systems into well-isolated components that allow us to leave as many options open as possible, for as long as possible.

- A good architecture makes the system easy to change, in all the ways that it must change, by leaving options open.

Decoupling Layers

- The architect wants the structure of the system to support all the necessary use cases, but does not know what all those use cases are.

- The architect does not know the basic intent of the system, so he can emply the Single Responsibility Principle and the Common Closure Principle to separate those things that change for different reasons, and to collect those things that change for the same reasons, given the context of the intent of the system.

- Thus we find the system divided into decoupled horizontal layers:

- UI

- Application specific business rules

- Application independent business rules

- Database etc..

Decoupling Use Cases

- Some use cases will change at a different rate and for different reasons than other use cases.

- Each use case uses some UI, some application-sepecific business rules, some application-independent business rules, and some database functionality.

→ As we are dividing the system in to horizontal layers, we are also dividing the system into thin vertical use cases that cut through those layers. - To achieve decoupling, we separate the UI of the add-order use case from the UI of the delete-order use case. Same thing with the business rules, and with the database.

- If you decouple the elements of the system that change for different reasons, then you can continue to add new use cases without interfering with old ones.

Independent Develop-Ability

- When components are strongly decoupled, the interference between teams is mitigated.

- If the business rules don't know about the UI, then a team that focues on the UI cannot much affect a team that focuses on the business rules.

- So long as the layers and use cases are decoupled, the architecture of the system will support the organization of the teams, irrespective of whether they are organized as feature teams, component teams, layer teams, or some other variation.

Independent Deploy-Ability

- The decoupling of the use cases and layers also affords a high degree of flexibility in deployment.

- If the decoupling is done well, then it should be possible to hot-swap layers and use cases in running systems.

Duplication

- Architects often fall into a trap that hinges on their fear of duplication.

- There are different kinds of duplication:

- True duplication: every change to one instance necessitates the same change to every duplicate of that instanc.

- False/accidental duplication: If two apparently duplicated sections of code evolve along different paths. If they change at different rates, and for different reasons, then they are not true duplicates.

- Duplication is almost certainly accidental. Creating the separate view model is not a lot of effort, and it will help you keep the layers properly decoupled.

Decoupling Modes

- If the UI and the database have been separated from business rules, then they can run in different servers.

- The decoupling that we did for the same of the use cases also helps with operations. But, to take advantage of the operational benefit, the decoupling must have the appropriate mode.

- Sometimes we have to separate our components all the way to the service level.

- A good architecture leaves options open. The decoupling mode is one of those options.

- Layers and use cases can be decoupled at the source code level, at the deployment level, and at the service level:

- Source level: We can control the dependencies between source code modules so that changes to one module do not force changes or recompilation of others.

In some decoupling modes, all the components execute in the same address space, and communicate with each other using simple function calls.- Deployment level: We can control the dependencies between deployable units like shared libraries, so that changes to the source code in one module do not force others to be rebuilt and redeployed.

While many components live in the same address space, and communicate through function calls, other components live in other precesses in the same processor, and communicate through interprocess communications, sockets, or shared memory. The important thing here is that the decoupled components are partitioned into independently deployable units.- Service level: We can reduce the dependencies down to the level of data structures, and communicate solely through network packets.

What is the best decoupling mode to use?

- It's hard to know which mode is best during the early phases of a project. As the project matures, the optimal mode may change.

- A good architecture will allow a system to be born as a monolith, deployed in a single file, but then to grow into a set of independently deployable units, and then all the way to independent services and/or micro-services.

- A good architecture protects the majority of the source code from those changes. It leaves the decoupling mode open as an option so that large deployments can use one mode, whereas small deployments can use another.

#17 Boundaries: Drawing Lines

- Boundaries separate software elements from one another, and restrict those on one side from knowing about those on the other.

- Some of the boundaries are drawn before any code is written in the project for the purposes of deferring decisions for as long as possible, and some others are drawn much later.

- Premature decisions are the decisions that have nothing to do with the business requirements (use cases) of the system.

Which lines do you draw, and when do you draw them?

- You draw lines between things that matter and things that don't.

- The database doesn't matter to the business rules, so there should be a line between them: the database knows about the business rules. The business rules do not know about the database. This implies that the database interface classes live in the business rules component, while the database access classes live in the database component.

What about input and output?

- We often think about the behavior of the system in terms of the behavior of the I/O: Behind a video game interface there is a sophisticated set of data structures and functions driving it. That model does not need the interface. I would execute its duties, modeling all the events in the game, without the game ever displayed on the screen.

→ The interface does not matter to the model (aka business rules).

Plugin architectrure

- Taking decisions about making boundaries between business rules and the database, and another between business rules and the interface create a kind of pattern for the addition of other components. That pattern is the same pattern that is used by systems that allow third party plugins.

- With those decisions we have made it possible to plug in many different kinds of user interfaces. Same is true of the database, we can replace it with any of the various SQL databases, or NoSQL database etc.

The plugin argument

- Arranging our systems into a plugin architecture creates firewalls across which changes cannot propagate.

- Boudaries are drawn where there is an axis of change.

- Business rules changes at different times and for different reasons than dependency injection frameworks, so there should be a boundary between them.

→ This is SRP (Single Responsibility Principle) again. It tells us where to draw our boundaries.

#18 Boundary Anatomy

Boundaries come in many different forms.

Boundary crossing

- Boundary crossing is nothing more than a function on one side of the boundary calling a function on the other side and passing along some data.

- To create an appropriate boundary crossing is to manage the source code dependencies because when one source code module changes, other source code modles may have to be changed or recompiled, and redeployed.

The dreaded monolith

- The simplest (and most common) of the architectural boundaries is those who has no strict physical representation.

- It's a disciplined segregation of functions and data within a single processor and a single address space (aka the source-level decoupling mode).

- The fact that the boundaries are not visible during the deployment of a monolith does not mean that they are not present and meaningful.

- Communication between components in a monolith are very fast and inexpensive. Consequently, communications across source-level decoupled boundaries can be very chatty.

Deployment components

- The simplest physical representation of an architectural boundary is a dynamically linked library like a Java jar file.

- Deployment does not involve compilation. Instead, the components are delivered in binary, or some equivalent deployable form.

→ This is the deployment-level decoupling mode. - With that one exception, deployment-level components are the same as monoliths.

Threads

Both monoliths and deployment components can make use of threads. Threads are not architectural boundaries or units of deployment, but rather a way to organize the schedule and order of execution.

Local processes

- A local process is a much stronger physical architectural boundary. Its typically created from the command line or an equivalent system call.

- Local processes run in the same processor, or in the same set of processors within a multicore, but run in separate address spaces.

- Local processes communicate with each other using sockets, or some other kind of operating system communications facility such as mailboxes or message queues.

- The segregation strategy between local processes is the same as for monoliths and library compoenents. Source Code dependencies point in the same direction across the boundary, and always toward the higher level component.

Services

- A service is the strongest boundary. It's a process, genrally started from the command line or through an equivalent system call and it do not depend on its physical location.

- Two communicating services may, or may not, operate in the same physical processor or multicore. The services assume that all communications take place over the network.

- Communications across service boundaries are very slow compared to function calls.

- The same rules apply to services as apply to local processes Lower-level services should “plug in” to higher-level services.

#19 Policy and Level

Software systems are statements of policy.

- Some those statements will describe how particular business rules are to be calculated. Others will describe how certain reports are to be formatted. Still others will describe how input data are to be validated.

Level

- A level is the distance from the inputs and outputs.

- The farther a policy is from both the inputs and the outputs of the system, the higher its level. The policies that manage input and output are the lowest-level policies in the system.

#20 Business Rules

- Business rules are rules or procedures that make or save the business money. These rules would make or save the business money.

Entities

- An entity is an object within our computer system that embodies a small set of business rules operating on business data.

- The entity object either contains the business data or has very easy access to that data.

- The interface of the entity consists of the functions that implement the business rules that operate on that data.

Use cases

- Not all business rules are as pure as Entities. Some business rules make or save money for the business by defining and constraining the way that an automated system operates. These rules would not be used in a manual environment, because they make sense only as part of an automated system.

- A use case is a description of the way that an automated system is used. It specifies the input to be provided by the user, the output to be returned to the user, and the processing steps involved in producing that output.

- Use cases contain the rules that specify how and when the business rules within the entities are invoked. Use cases control the dance of the entities.

- A use case is an object. It has one or more functions that implement the application-specific business rules.

- Entities have no knowledge of the use cases that control them.

→ This is another example of the direction of the dependencies following the Dpendency Inversion Principle. - Entities are high level and use cases are lower level because use cases are specific to a single application, and therefore, are closer to the inputs and outputs of that system while entities are generalizations that can be used in many different applications, so they are farther from the inputs and outputs of the system.

→ Use cases depend on the Entities, Entities do not depend on use cases.

Request and Response Models

- Use cases should handle input and output data independently.

- A well-formed use case object should be unaware of the communication method to the user or other components.

- Use case class accepts simple request data structures for input and returns simple response data structures, avoiding dependencies on specific frameworks.

- Request and response models should not derive from standard framework interfaces to ensure independence.

- The lack of dependencies is crucial to prevent indirect binding of use cases to external dependencies.

- Avoid including references to Entity objects in data structures as their purposes and evolution are different.

- Tying Entities and request/response models violates Common Closure and Single Responsibility Principles.

- Connecting them leads to tramp data and conditional code, hindering maintainability.

#21 Screaming Architecture

What does the architecture of your application scream? When you look at the top-level directory structure, and the source files in the highest-level package, do they scream "Health Care System" ? or "Rails, Spring/Hibernate etc..." ?

The Theme of an Architecture

Architectures are not (or should not be) about frameworks. Architectures should not be supplied by frameworks. Frameworks are tools to be used, not architectures to be conformed to. If your architecture is based on frameworks, then it cannot be based on your use cases.

The Purpose of an Architecture

Good architectures are centered on use cases so that architects can safely describe the structures that support those use cases without committing to frameworks, tools, and environments.

A good software architecture allows decisions about frameworks, databases, web servers, and other environmental issues and tools to be deferred and delayed. Frameworks are options to be left open.

A good architecture makes it easy to change your mind about those decisions, too. A good architecture emphasizes the use cases and decouples them from peripheral concerns.

But What About The Web

The fact that your system is delivered on the web does not dictate the architecture of your system.

The web is an I/O device and your application architecutre should treat it as such. The fact that your application is delivered over the web is a detail and should not dominate your system structure. Your system architecture should be as ignorant as possible about how it will be delivered.

Frameworks are Tools, not Ways of Life

Look at each framework with a jaded eye. View it skeptically. Yes, it might help, but at what cost? Ask yourself how you should use it, and how you should protect yourself from it. Think about how you can preserve the use-case emphasis of your architecture. Develop a strategy that prevents the framework from taking over that architecture.

Testable Architectures

If your system architecture is all about the use cases, and if you have kept your frameworks at arm’s length, then you should be able to unit-test all those use cases without any of the frameworks in place.

Your Entity objects should be plain old objects that have no dependencies on frameworks or databases or other complications. Your use case objects should coordinate your Entity objects.

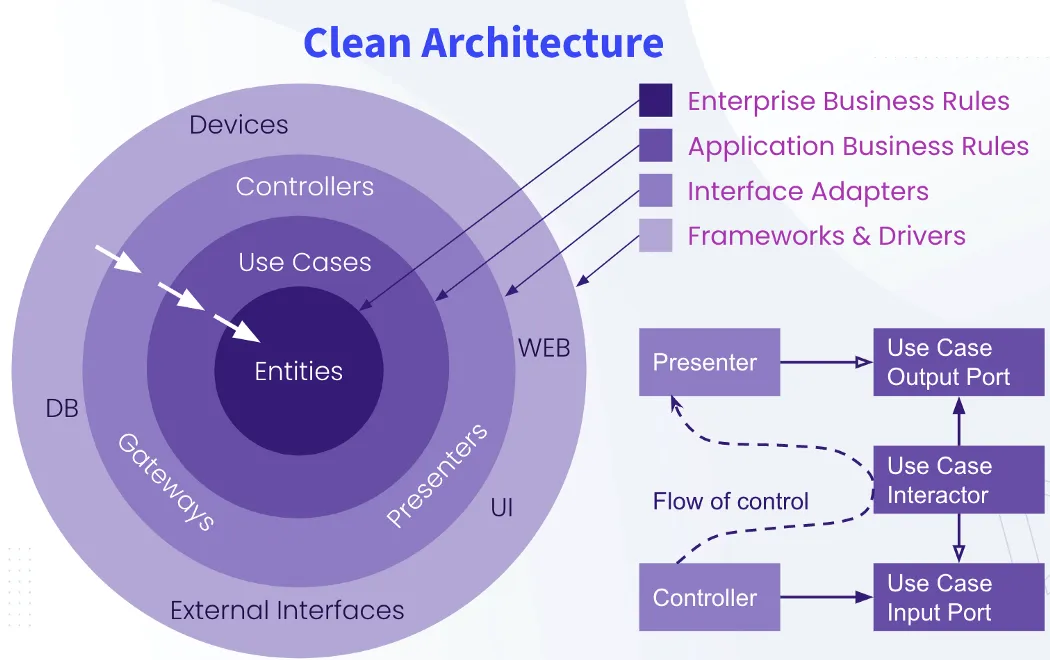

#22 The Clean Architecture

Over the last several decades we’ve seen a whole range of ideas regarding the architecture of systems: Hexagonal Architecture (also known as Ports and Adapters), DCI, BCE etc...

Although these architectures all vary somewhat in their details, they are very similar. They all have the same objective, which is the separation of concerns. They all achieve this separation by dividing the software into layers. Each has at least one layer for business rules, and another layer for user and system interfaces.

These architectures are:

- Independent of frameworks.

- Testable.

- Independent of the UI.

- Independent of the database.

- Independent of any external agency.

The Dependency Rule

In general, the further in you go, the higher level the software becomes. The outer circles are mechanisms. The inner circles are policies. The overriding rule that makes this architecture work is the Dependency Rule:

Source code dependencies must point only inward, toward higher-level policies.

Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle. In particular, the name of something declared in an outer circle must not be mentioned by the code in an inner circle. That includes functions, classes, variables, or any other named software entity.

By the same token, data formats declared in an outer circle should not be used by an inner circle, especially if those formats are generated by a framework in an outer circle. We don’t want anything in an outer circle to impact the inner circles.

Entities

An entity can be an object with methods, or it can be a set of data structures and functions. They encapsulate the most general and high-level rules. They are the least likely to change when something external changes. No operational change to any particular application should affect the entity layer.

Use Cases

The use cases orchestrate the flow of data to and from the entities, and direct those entities to use their Critical Business Rules to achieve the goals of the use case.

We do not expect changes in this layer to affect the entities. We also do not expect this layer to be affected by changes to externalities such as the database, the UI, or any of the common frameworks.

We do, however, expect that changes to the operation of the application will affect the use cases and, therefore, the software in this layer. If the details of a use case change, then some code in this layer will certainly be affected.

Interface Adapters

The software in the interface adapters layer is a set of adapters that convert data from the format most convenient for the use cases and entities, to the format most convenient for some external agency such as the database or the web.

Similarly, data is converted, in this layer, from the form most convenient for entities and use cases, to the form most convenient for whatever persistence framework is being used (i.e., the database).

No code inward of this circle should know anything at all about the database.

Frameworks And Drivers

Generally you don’t write much code in the frameworks and drivers layer, other than glue code that communicates to the next circle inward. It is where all the details go. The web is a detail. The database is a detail. We keep these things on the outside where they can do little harm.

Only Four Circles?

There’s no rule that says you must always have just these four. However, the Dependency Rule always applies. Source code dependencies always point inward. As you move inward, the level of abstraction and policy increases. The outermost circle consists of low-level concrete details. As you move inward, the software grows more abstract and encapsulates higherlevel policies. The innermost circle is the most general and highest level.

Crossing Boundaries

We usually resolve this apparent contradiction by using the Dependency Inversion Principle. In a language like Java, for example, we would arrange interfaces and inheritance relationships such that the source code dependencies oppose the flow of control at just the right points across the boundary.

The same technique is used to cross all the boundaries in the architectures. We take advantage of dynamic polymorphism to create source code dependencies that oppose the flow of control so that we can conform to the Dependency Rule, no matter which direction the flow of control travels

Which Data Crosses The Boundaries

Typically the data that crosses the boundaries consists of simple data structures.

You can use basic structs or simple data transfer objects if you like. Or the data can simply be arguments in function calls. Or you can pack it into a hashmap, or construct it into an object. The important thing is that isolated, simple data structures are passed across the boundaries.

When we pass data across a boundary, it is always in the form that is most convenient for the inner circle.

#23 Presenters and Humble Objects

The Humble Object Pattern

The Humble Object pattern is a design pattern that was originally identified as a way to help unit testers to separate behaviors that are hard to test from behaviors that are easy to test. → Split the behaviors into two modules or classes:

- The humble module: it contains all the hard-totest behaviors stripped down to their barest essence.

- The other module: it contains all the testable behaviors that were stripped out of the humble object.

For example, GUIs are hard to unit test because it is very difficult to write tests that can see the screen and check that the appropriate elements are displayed there. However, most of the behavior of a GUI is, in fact, easy to test

Presenters and Views

- The View is the humble object that is hard to test. The code in this object is kept as simple as possible. It moves data into the GUI but does not process that data.

- The Presenter is the testable object. Its job is to accept data from the application and format it for presentation so that the View can simply move it to the screen.

For example, if the application wants a date displayed in a field, it will hand the Presenter a Date object.

The Presenter will then format that data into an appropriate string and place it in a simple data structure called the View Model, where the View can find it.

Testing and Architecture

The separation of the behaviors into testable and non-testable parts in the Humble Object pattern often defines an architectural boundary. The Presenter/View boundary is one of these boundaries, but there are many others.

Database Gateways

Between the use case interactors and the database are the database gateways. These gateways are polymorphic interfaces that contain methods for every create, read, update, or delete operation that can be performed by the application on the database.

Data Mappers

There is no such thing as an object relational mapper (ORM) because objects are not data structures. At least, they are not data structures from their users’ point of view. The users of an object cannot see the data, since it is all private. Those users see only the public methods of that object. So, from the user’s point of view, an object is simply a set of operations. A data structure, in contrast, is a set of public data variables that have no implied behavior. ORMs would be better named “data mappers,” because they load data into data structures from relational database tables. ORM systems reside in the database layer. ORMs form another kind of Humble Object boundary between the gateway interfaces and the database.

Service Listeners

The application will load data into simple data structures and then pass those structures across the boundary to modules that properly format the data and send it to external services. On the input side, the service listeners will receive data from the service interface and format it into a simple data structure that can be used by the application. That data structure is then passed across the service boundary.

#24 Partial Boundaries

Full-fledged architectural boundaries require reciprocal polymorphic Boundary interfaces, Input and Output data structures, and all of the dependency management necessary to isolate the two sides into independently compilable and deployable components.

This kind of anticipatory design is often frowned upon by many in the agile community as a violation of YAGNI (you aren't going to need it) and that's where the implementation of partial boundary may come.

Skip the latest step

- A partial boundary can be constructed by creating independently compilable and deployable components, but keeping them together in the same component.

- This approach requires the same amount of code and design work as a full boundary, but without the need for managing multiple components.

- There's no need for version number tracking or release management, which is a significant advantage.

Facades

An even simpler boundary is the Facade pattern, In this case, even the dependency inversion is sacrificed. The boundary is simply defined by the Facade class, which lists all the services as methods, and deploys the service calls to classes that the client is not supposed to access.

Note, however, that the Client has a transitive dependency on all those service classes. In static languages, a change to the source code in one of the Service classes will force the Client to recompile. Also, you can imagine how easy backchannels are to create with this structure.

Layers and Boundaries

System can be composed of three components: UI, business rules, and database. For some simple systems, this is sufficient. For most systems, though, the number of components is larger than that.

Architectural boundaries exist everywhere.

We, as architects, must be careful to recognize when they are needed. We also have to be aware that such boundaries, when fully implemented, are expensive.

At the same time, we have to recognize that when such boundaries are ignored, they are very expensive to add in later—even in the presence of comprehensive test-suites and refactoring discipline.

So what do we do, we architects? The answer is dissatisfying. On the one hand, some very smart people have told us, over the years, that we should not anticipate the need for abstraction. This is the philosophy of YAGNI: “You aren’t going to need it.” There is wisdom in this message, since over-engineering is often much worse than under-engineering. On the other hand, when you discover that you truly do need an architectural boundary where none exists, the costs and risks can be very high to add such a boundary.

#26 The main Component

In every system, there is at least one component that creates, coordinates, and oversees the others.

The ultimate detail

The Main component is the ultimate detail—the lowest-level policy. It is the

initial entry point of the system. Nothing, other than the operating system,

depends on it.

Its job is to create all the Factories, Strategies, and other global facilities, and then hand control over to the high-level abstract portions of the system.

It is in this Main component that dependencies should be injected by a Dependency Injection framework. Once they are injected into Main, Main should distribute those dependencies normally, without using the framework.

Think of Main as the dirtiest of all the dirty components.

The point is that Main is a dirty low-level module in the outermost circle of the clean architecture. It loads everything up for the high level system, and then hands control over to it

#27 Services: Great and Small

• Services seem to be strongly decoupled from each other. As we shall see, this is only partially true.

• Services appear to support independence of development and deployment.

Again, as we shall see, this is only partially true.

Service architecture?

The architecture of a system is defined by boundaries that separate high-level policy from low-level detail and follow the Dependency Rule. Services that simply separate application behaviors are little more than expensive function calls, and are not necessarily architecturally significant.

There are often substantial benefits to creating services that separate functionality across processes and platforms—whether they obey the Dependency Rule or not. It’s just that services, in and of themselves, do not define an architecture.

Services are, after all, just function calls across process and/or platform boundaries. Some of those services are architecturally significant, and some aren’t.

Service Benefits?

The decoupling fallacy

Services are strongly decoupled from each other. After all, each service runs in a different process, or even a different processor; therefore those services do not have access to each other’s variables.

Services are decoupled at the level of individual variables. However, they can still be coupled by shared resources within a processor, or on the network. What’s more, they are strongly coupled by the data they share.

As for interfaces being well defined, that’s certainly true—but it is no less true for functions. Service interfaces are no more formal, no more rigorous, and no better defined than function interfaces. Clearly, then, this benefit is something of an illusion.

The fallacy of independent development and deployment

Services can be managed by dedicated teams, allowing for independent development, deployment, and operation. This model is believed to enable scalability, with large systems potentially consisting of hundreds or thousands of services managed by separate teams. However there are two caveats: Firstly, service-based systems are not the only scalable solution, as history has shown that large systems can also be built from monoliths and component-based systems. Secondly, the concept of complete independence in service-based systems is challenged by the ‘decoupling fallacy’. Services that are interconnected by data or behavior cannot be entirely independent; their development, deployment, and operation must be coordinated.

As useful as services are to the scalability and develop-ability of a system, they are not, in and of themselves, architecturally significant elements.

The architecture of a system is defined by the boundaries drawn within that system, and by the dependencies that cross those boundaries. That architecture is not defined by the physical mechanisms by which elements communicate and execute.

A service might be a single component, completely surrounded by an architectural boundary. Alternatively, a service might be composed of several components separated by architectural boundaries.

#28 The Test Boundary

Tests are part of the system, and they participate in the architecture just like every other part of the system does. In some ways, that participation is pretty normal. In other ways, it can be pretty unique.

Tests as System Components

- From an architectural point of view, all tests are the same.

- Tests, by their very nature, follow the Dependency Rule; they are very detailed and concrete; and they always depend inward toward the code being tested.

- Tests are the most isolated system component. They are not necessary for system operation. No user depends on them. Their role is to support development, not operation. And yet, they are no less a system component than any other.

Design For Testability

- Tests that are not well integrated into the design of the system tend to be fragile, and they make the system rigid and difficult to change.

- Tests that are strongly coupled to the system must change along with the system. Even the most trivial change to a system component can cause many coupled tests to break or require changes.

- Test suites that operate the system through the GUI must be fragile. Therefore design the system, and the tests, so that business rules can be tested without using the GUI.

The Testing API

- The purpose of the testing API is to decouple the tests from the application. This decoupling encompasses more than just detaching the tests from the UI: The goal is to decouple the structure of the tests from the structure of the application.

#29 Clean Embedded Architecture

"Although software does not wear out, firmware and hardware become obsolete, thereby requiring software modifications." - James Grenning

"Although software does not wear out, it can be destroyed from within by unmanaged dependencies on firmware and hardware" - James Grenning

These notes were written by Ayoub Abidi

These notes were spell-checked by Majdi Zlitni